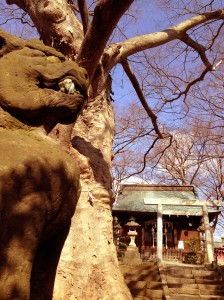

A hung wooden mask and Wisteria at Asakakunitsuko Shrine, just off the main Sakura dori in Koriyama, Japan

During my few years teaching ESL, I’ve encountered the same lessons again and again – comparatives, conditionals, relative clauses, and so on. Although it might sound monotonous, it’s a fun and rewarding challenge teaching the same topics over and over, each time tweaking what didn’t work the last time and adding more creative touches for improvement. As a teacher and a traveler, though, the best lesson topic is superlatives; there are loads of creative ways to teach such a subject, and the information you can mine from students regarding the best local digs and sights is, and has been, immensely valuable.

In my final days of teaching in Japan, my students asked me what I would miss most about Koriyama. It was a good chance to thank them for all of their recommendations over the year I had the privilege of being their teacher.

Thanks to their thought-provoking question and a recent serendipitous Sunday drive with a former coworker, I found myself again in Jodomatsu Park, undoubtedly one of the most beautiful and peaceful places in the city. Although it’s quite some distance from downtown, the park is dear to me because it is, in fact, not very “park-like” compared to Koriyama’s other green spaces. You’ll find few paved paths, most of which look like gullies cut deep by years of rainfall down their steep, loose-soiled slopes.

The park is namely famous for its mushroom-like stone structures, known as hoodoos – although in this case, “was” would be more appropriate, as many of the hard-rock caps were toppled by the 2011 Great Tohoku Earthquake. Along the way, you’ll find wide, shaded areas of Epimedium (Viagra plant!), with its charming heart-shaped leaves and strangely gorgeous dangling flowers, and be rewarded for your uphill troubles with a scenic topiary of pastel pinks among the green.

Another favorite of the Koriyama countryside is Miharu (三春). As I wrote about before, this area in Tamura district is worth visiting just for its simple, rural beauty. Attraction-wise, it’s home to Takizakura (三春滝桜) and famed for Deko-yashiki, shops specializing in hand-carved wood products including Daruma dolls, wooden horses, long-nosed tengu masks, and other folk crafts. Here, you can watch as the artisans whittle away and delicately paint these unique figurines. In May, the town holds the annual Children’s Day parade, at which participants clad in colorful kimonos and period clothing stroll and dance down Miharu’s main street.

To top it off, Miharu Herb Hana Garden is a pleasant stop for plant and ice cream lovers (though my gluten allergy prevented me from indulging, my friend said she enjoyed her light-purple lavender cone).

For someone with time to kill in Koriyama but not enough to journey far from the city center, there are two short walks I recommend and which I’ve highlighted on the izi.Travel app. One of these tree-lined, creekside paths stems from Kaiseizan Park and meanders past Koriyama Women’s University. Lilacs, Daphnes, and Wisterias color and scent the way in springtime, leading to bursting blue and purple hydrangeas in summer, and deep-red, downy Japanese maples in the autumnal months.

Also within walking distance of downtown is a favorite sacred place of mine which I visit nearly every day – Atago Shrine. Although small, the shrine is sheltered by a far more impressive presence, a massive tree smoothed down by the ages and shrine goers. Another favorite shrine, which I visit seldom as it’s quite some ways from downtown, is Otsukikasuga Shrine. This shrine is impressive not only for its location, the pristine neighborhood of which is the dream of gingko nut lovers (or the nightmare of gingko nut despisers), but also for the impressive height of the numerous cedars that dominate the small hillside on which the many komainu–guarded shrine itself rests.

Not far from Atago Shrine is the second longest river in the Tōhoku region of Japan, Abukuma River. The shallow waterway hugs around Koriyama’s inner belly and is flanked by rows of cherry trees fluttering their pink petals in spring. I often run on the riverside paths or spend some time in one of the adjacent parks, watching the fisherman and cranes, both of whom never seem to catch any of the massive carp lolling about along the river bottom.

I have little in the way of food recommendations, but a recent obsession of mine has been Kappazushi, a chain of conveyor-belt sushi restaurants (kaiten-zushi) in Japan. After a sushi order is placed via touch computer, a model bullet train (shinkansen) whizzes out along the top track with your dish. Endless joy for a child like me. For all-you-can-drink (nomihoudai) establishments, I recommend the eclectic Hanbe, while Toranokaze is a pleasant place for a drink, small pizza, and smoke stench requiring at least two laundry washes.

Last, and perhaps most obvious, on the list is the Koriyama Big-I, the large gray orb on the top floors of which is a planetarium and a damn good view of the city and its surrounding mountains. I admit that I wasn’t entirely impressed on my first ascent, looking out on the sprawling city, but after my year spent here, I’ve found the best places can only be found either with patience or the help of some truly excellent and kind people.